The Real Food Fallacy: What the New Dietary Guidelines Get Wrong

The updated USDA guidelines elevate meat, dairy, and protein—but that framing contradicts decades of nutrition evidence.

Key Takeaways

The new dietary guidelines correctly identify chronic disease as a national crisis.

They place primary blame on highly processed foods while promoting meat and dairy as foods to eat more often.

This contradicts strong evidence linking saturated fat and cholesterol, found largely in animal foods, to heart disease and other chronic conditions.

Most Americans already get enough protein; protein deficiency is not driving today’s health crisis.

Diets centered on whole, plant-based foods remain the most consistently supported approach for preventing and reversing chronic disease.

A Familiar Problem, Framed the Wrong Way

The newly released Dietary Guidelines for Americans identify a reality most health professionals agree on: chronic disease is overwhelming the U.S. healthcare system.

“I have been telling people for years that 86% of healthcare costs are basically optional” Rochester Lifestyle Medicine Institute (RLMI) Founder, Dr. Ted Barnett said in a conversation with Roundstone Insurance CEO Mike Schroeder last fall, “They're self-induced chronic illnesses like diabetes, heart disease, stroke.”

That framing is not controversial. It reflects decades of public health data and everyday clinical experience.

The guidelines, however, rely heavily on the assumption that “real” or “whole” foods are inherently healthier, and that processing itself explains chronic disease. The evidence tells a more complicated story.

What the New Guidelines Emphasize

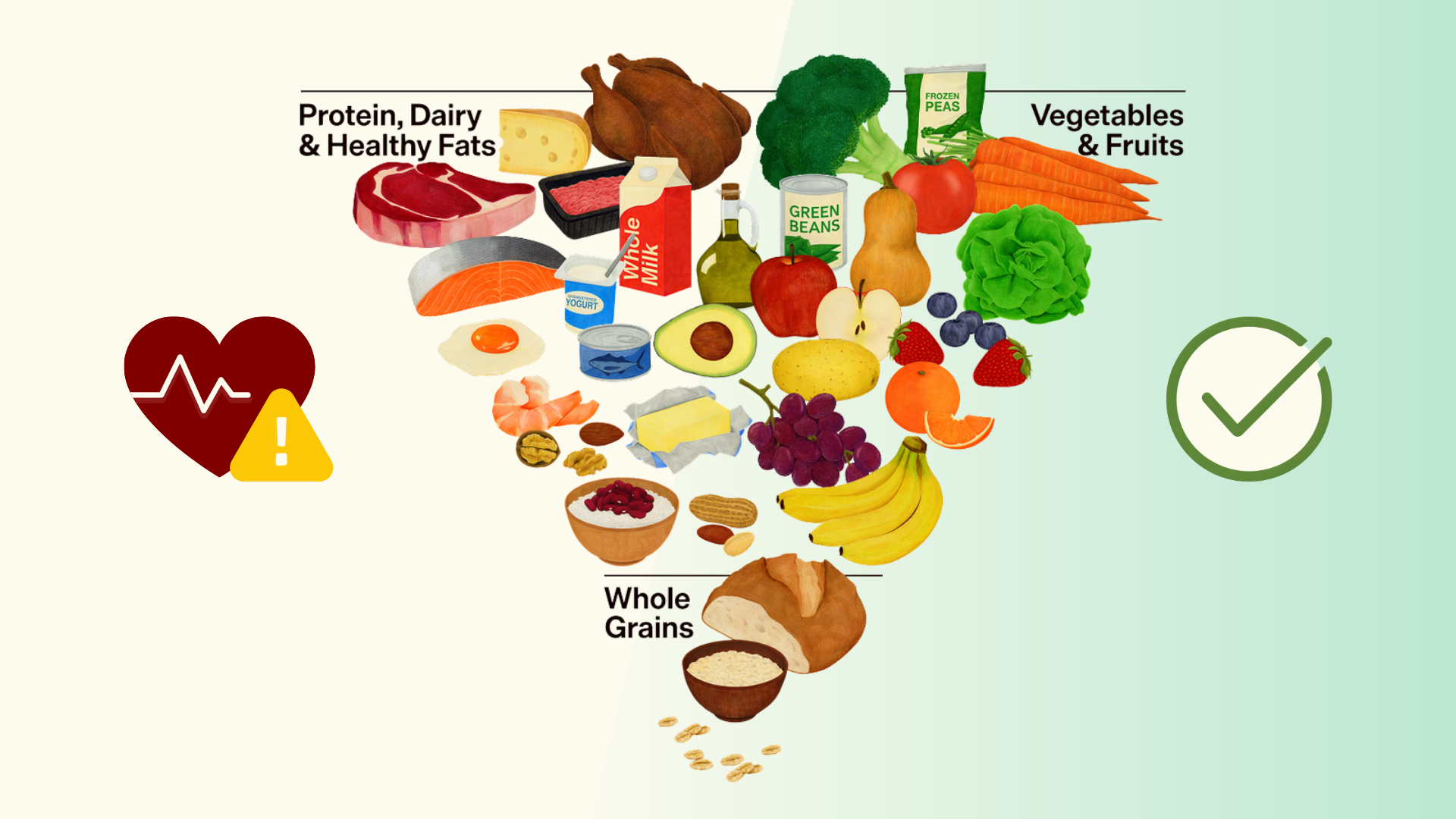

The updated guidelines, released under Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., introduce a revised food pyramid and a clear shift in messaging.

They place strong emphasis on three ideas:

Highly processed foods are presented as the primary dietary cause of chronic disease

Protein is positioned as a central nutritional priority

Meat, cheese, and full-fat dairy are elevated as foods to prioritize

This framing has drawn criticism from health experts who argue that it fails to clearly address the role of animal foods in chronic disease.

The Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine raised this concern directly. Its president, Neal Barnard, MD, FACC, stated:

“The guidelines are right to limit cholesterol-raising saturated (‘bad’) fat. But they should spell out where it comes from: dairy products and meat, primarily. And here the Guidelines err in promoting meat and dairy products, which are principal drivers of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity.”

PCRM has since formally petitioned federal agencies to withdraw and reissue the guidelines, citing longstanding concerns about industry influence from meat and dairy interests and conflicts with the scientific evidence.

This critique sets the stage for a closer look at the assumptions behind the new recommendations, particularly the renewed emphasis on protein and animal-based foods.

Are Americans Really Not Eating Enough Animal Protein?

The new guidelines recommend a daily protein target of 1.2 to 1.6 grams per kilogram of body weight. For a 150-pound adult, that equals roughly 80 to 120 grams of protein per day, substantially higher than previous federal recommendations for basic nutritional needs.

That emphasis implies that inadequate protein intake, and by extension inadequate intake of animal foods, is a meaningful contributor to today’s chronic disease burden.

The evidence does not support that conclusion.

Most Americans already meet or exceed their protein needs. The typical U.S. diet is centered around animal foods, with meat and dairy appearing at most meals. Prioritizing these foods even more, whether in processed or “whole” form, does not address the dietary factors most consistently linked to chronic disease.

It also overlooks a far more common and well-documented deficiency. As RLMI Medical Director, Dr. Kerry Graff notes:

“The dietary guidelines don’t address the fact that 97% of Americans currently get inadequate amounts of fiber, which is only found in whole plants. The diet they propose would not provide adequate fiber intake. Switching at least some protein intake from dairy and red meat to beans would, however.”

Taken together, this points to a different problem: diets that emphasize animal protein tend to crowd out fiber-rich foods while increasing saturated fat and cholesterol.

What the Science Actually Shows

When researchers study diet and long-term health outcomes, the most consistent findings are not about food processing categories. They are about dietary patterns and specific nutrients.

Across decades of research, several relationships are well established:

Saturated fat raises LDL (“bad”) cholesterol

Elevated LDL cholesterol is a direct cause of heart disease

Red meat and full-fat dairy are major sources of saturated fat and dietary cholesterol in the U.S. diet

Higher intake of fiber-rich whole plant foods is consistently linked to lower risks of heart disease, Type 2 diabetes, and all-cause mortality

Diets centered on animal-based foods are associated with higher risks of heart disease, Type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers

These conclusions are reflected in large population studies, controlled trials, and reviews from organizations such as the American Heart Association and the National Institutes of Health.

Why Blaming Processing Misses the Bigger Picture

Some highly processed foods clearly undermine health, especially those high in fat, added sugars, sodium, and industrial additives. Reducing reliance on these foods makes sense.

The problem is that the new guidelines treat processing as the primary explanation for chronic disease, while at the same time encouraging greater intake of meat and dairy. That framing doesn’t reflect what the research actually shows.

In his recent Lifestyle as Medicine lecture, Michael Greger emphasized that ultra-processed foods are not all equal. When researchers separate them by type, much of the disease risk is driven by processed and ultra-processed animal products and sugary beverages, not by all processed foods across the board.

This distinction is illustrated in the Stanford SWAP-MEAT trial, which found that replacing animal meat with plant-based alternatives improved LDL cholesterol and other cardiometabolic markers, even though the plant-based options were technically more “processed.” One of the study’s lead researchers, Stanford nutrition scientist Christopher Gardner, has since criticized the new food pyramid, saying:

“I’m very disappointed in the new pyramid that features red meat and saturated fat sources at the very top, as if that’s something to prioritize. It does go against decades and decades of evidence and research.”

That tension between the guidelines and the evidence raises a practical question: what would dietary guidance look like if it were built around long-term health outcomes instead?

What an Evidence-Based Response Looks Like

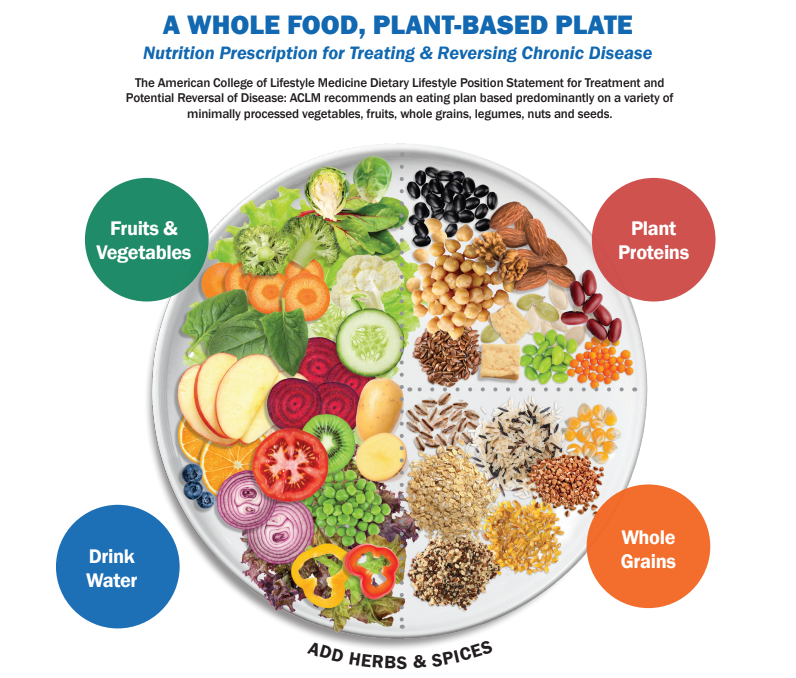

Across populations, cultures, and study designs, the evidence consistently supports dietary patterns that:

Center meals on vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds

Limit saturated fat and dietary cholesterol

Meet protein needs through adequate consumption of a variety of whole plant foods

Reduce risk of chronic disease while supporting overall health

This is the foundation of whole-food, plant-based nutrition and lifestyle medicine, and is reflected in the American College of Lifestyle Medicine (ACLM) Nutrition Prescription for Treating and Reversing Chronic Disease.

This approach is not about perfection or restriction. It is about aligning dietary guidance with what consistently improves long-term health outcomes.

Cutting Through the Confusion

At Rochester Lifestyle Medicine Institute, our focus remains the same: helping people understand what the strongest evidence shows and how to apply it in real life.

The 15-Day Whole-Food Plant-Based Jumpstart

A structured program designed to help participants experience what works. Many see measurable improvements in just 15 days, while learning habits they can sustain long term.

Lifestyle Medicine Grand Rounds

Monthly, case-based discussions for clinicians and curious learners who want a deeper understanding of how lifestyle medicine applies across a wide range of patient scenarios.

The RLMI Community

A shared space for learning, discussion, and support. Especially when guidance is shifting, having access to evidence-based resources and informed conversation matters.

If the latest guidelines leave you with more questions than answers, you’re not alone. When nutrition advice feels conflicting, returning to what the evidence consistently shows is the clearest path forward.